When should you spay or neuter your dog? As soon as possible, right? Maybe not. Some new studies have come out recently that question the ideal time to spay or neuter a pet. The idea of spaying and neutering (we’ll refer to it as neutering for both sexes) came about due to issues with an out-of-control pet population. Shelters were overrun with unwanted dogs and cats, and huge numbers of unwanted pets were being euthanized. Preventing uncontrolled reproduction was essential. http://www.humanesociety.org/animal_community/resources/timelines/animal_sheltering

We also knew that neutered pets were less likely to roam (males can smell a female in heat a mile away!), show aggression, or pee on your things. The more we spayed and neutered the more we noticed a decline in mammary cancer and pyometra (pus-filled uterus); and removing ovaries and testicles eliminates the risk of ovarian and testicular cancers. We found neutered dogs also tended to live longer. http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0061082

Most veterinary clinics have traditionally recommended neutering pets prior to sexual maturity (so around 5-6 months of age) to avoid behaviors associated with sexually mature pets. It also dramatically reduces the risk of mammary cancer, and surgical complications are less likely in young puppies than large dogs. Shelters started neutering pets prior to adoption, as young as 8 weeks, because they found that owners were unlikely to bring the pet back later for the procedure, even if given vouchers to have it done for free. These young puppies recovered well and did great, and it was better to neuter early than have that pet come back with behavior issues, or even a litter of unexpected pups they couldn’t keep.

For a long time we have been aware of some negative effects of neutering, such as decreased metabolism leading to weight gain, and urinary incontinence in females. These are generally manageable conditions. There are also the concerns with anesthetic and surgical complications, which can range from minor inconveniences to the rare possibility of death.

The recent studies that have come out look at how neuter status relates to frequency of joint disease and incidence of certain cancers over the course of a pet’s lifetime. Many of the studies focus on individual breeds of dogs, and the results vary between breeds, therefore we cannot apply these results to mixed breed dogs or breeds that have not been studied. They are also retrospective studies, meaning researchers gathered data from pets previously seen at teaching hospitals (primarily UC-Davis). These studies varied in whether they addressed how old the pet was when neutered (<6 mo, 6mo-1 year, or >1 year), which also complicates comparisons. There are inherent issues with retrospective studies, including the fact that you can’t have a true control group. You can determine correlation of diseases to neuter status, but you cannot prove causation (Just because neutered pets have more hip dysplasia doesn’t necessarily mean that it is because they are neutered. There may be other factors involved). Also, because the data comes only from a teaching hospital means it may not be representative of the breed population as a whole.

Despite these inevitable flaws, several studies did find significant increases in cranial cruciate ligament (CCL) tears, hip dysplasia, and certain types of cancers in neutered vs. intact dogs. One study even looked at a correlation between neuter status and risk of immune mediated diseases. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5146839/

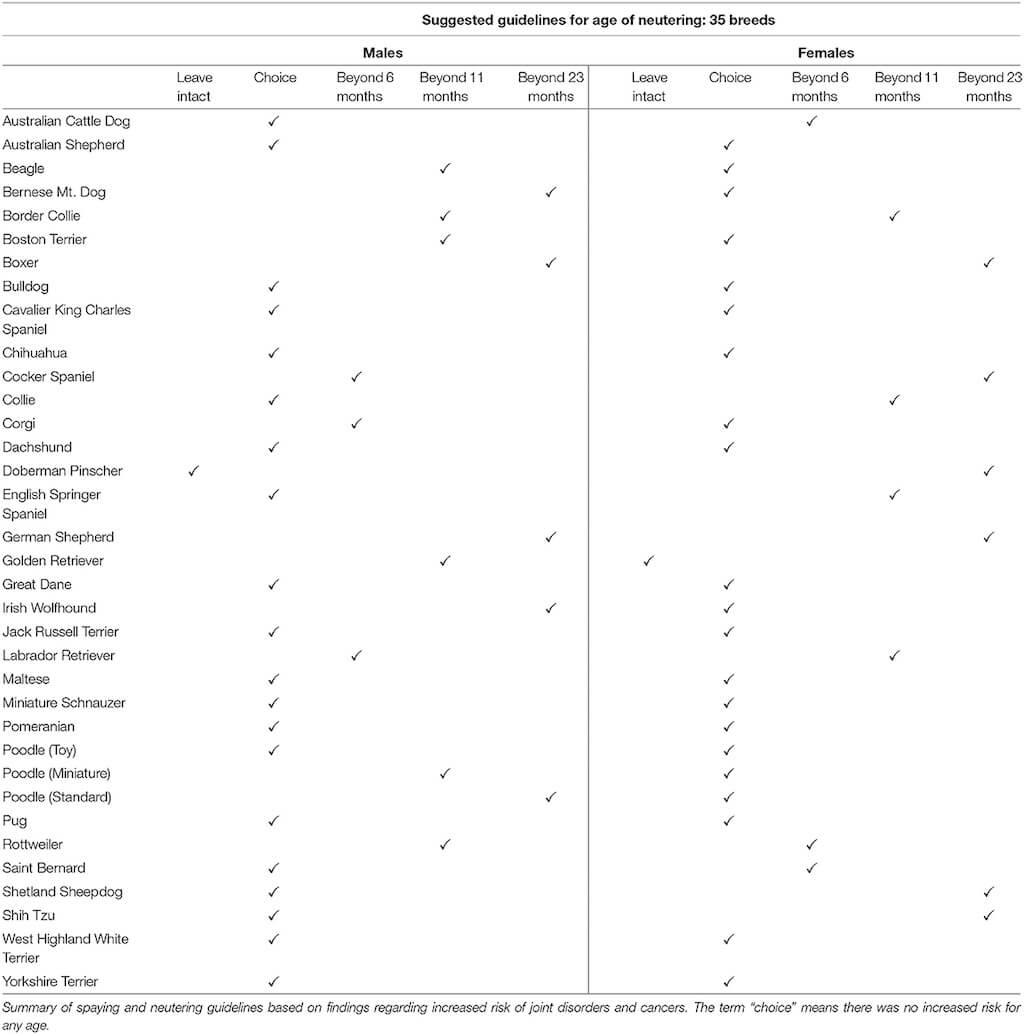

The following is a link to a comprehensive study from UC-Davis assessing 35 breeds of dogs, and a chart to summarize. If you have questions about when to neuter your own pet, please consult with your veterinarian to go over all the pros and cons. Keep in mind that these studies have created more questions than answers, so there may not always be a clear “right” answer.

UC-Davis Study: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fvets.2020.00388/full